‘What is Douay-Rheims version of the Bible? How does it differ from other translations?’

(question from a student, L.W.).

We thought it is best to answer with a chapter of the book Interpreting Scripture, titled ‘How to choose a Bible translation’, written by professor Tarsee Li, Ph.D, Oakwood University.

Translation [into a modern language] involves aiming at a moving target, which has accelerated over the centuries. English is developing more quickly today than at any time in its previous history. Some words have ceased to be used; others have changed their meanings. When a translation itself requires translation, it has ceased to serve its original purpose. (Alister McGrath, In the Beginning: The Story of the King James Bible, Hodder and Stoughton, 2001, pp. 308, 309.)

While the King James Bible is still one of the most widely used Bibles in the English-speaking world, its language is frequently no longer understood by modern people, particularly young people. The second half of the twentieth century, therefore, has seen a proliferation of modern Bible versions. While most of them have been produced by Protestant scholars, Roman Catholics, who in the past relied on the Douay Bible (published in 1609), have also produced a number of modern translations: The Knox Translation (1956), The Revised Standard Version: Catholic Edition (1966), The Jerusalem Bible (1966), The New American Bible (1970–83), The New Jerusalem Bible (1985), and The African Bible (1999). In contrast to the Protestant Bibles, the Catholic Bibles all include seven additional books, the Apocrypha (Tobit, Judith, Wisdom, Sirach, 1 and 2 Maccabees, and Baruch), as well as some additions to Daniel and Esther. Furthermore, “Canon Law” of the Roman Church requires all Bible versions to include explanatory notes.

While Protestant Bibles generally come without explanatory notes, a number of annotated Bibles and Study Bibles have been produced over the years. The controversial notes in the Scofield Reference Bible (1909) have most effectively promoted dispensationalism. Less controversial Study Bibles are The Thompson Chain Reference Bible (1908), The New Oxford Annotated Bible with Apocrypha (1973), The Life Application Bible with 10,000 notes (1991), and The Archaeological Study Bible (2005).

Evaluating Bible Translations

There is no substitute for reading the Bible in the original languages. But, when that is not possible, the best way to get as close to the original as possible is to read a number of different translations. The advantage of using various translations is that in this way we can catch a glimpse of the richness a word may have in the original Hebrew or Greek. Furthermore, different translations may provide different solutions to difficult texts.

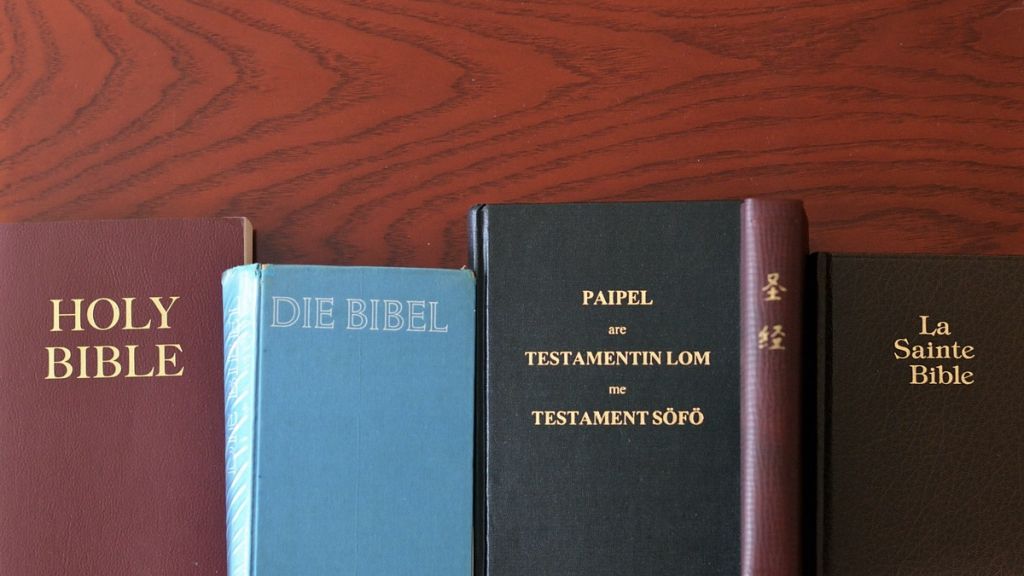

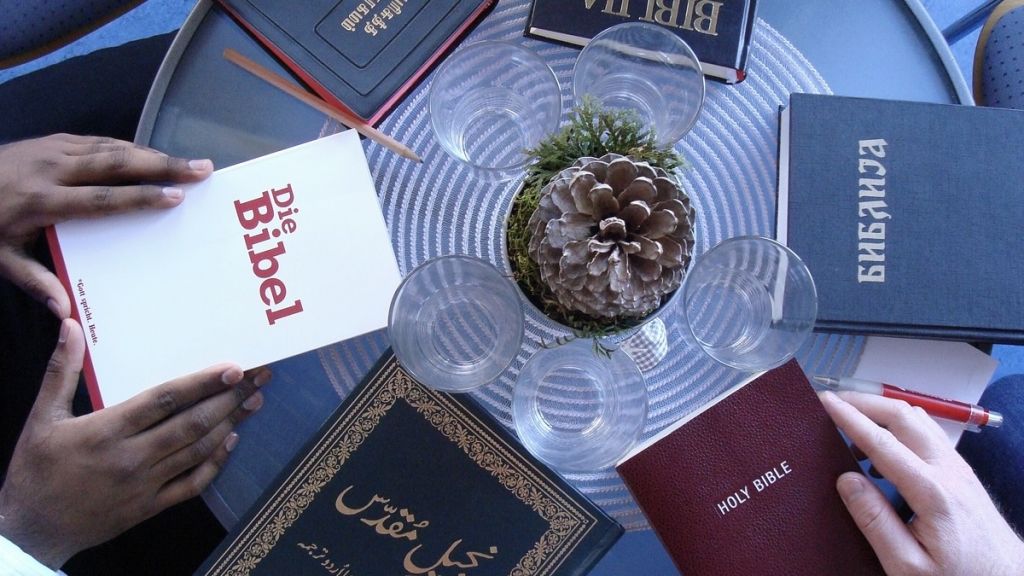

Bible Translations: The whole Bible has been translated into 429 languages, the New Testament into a further 1,144 languages and portions of the Bible into a further 862 languages, making a total of more than two thousand and four hundred languages. (Bible Society Record, Fall 2007, 8).

The proliferation of English versions in the twentieth century has made it necessary to carefully consider which translation one is going to use and for which purpose. Generally, the preface or introduction of a translation will explain the philosophy behind the translation, and it is useful to read it. Below is a brief outline of some of the major criteria by which Bible translations can be evaluated.

The type of translation

First, we need to recognise that there are two basic types of Bible translations:

(1) The formal equivalence or literal translation attempts to translate the text word for word as close as possible to the original, e.g., The King James Version (KJV 1611), The Revised Version (RV 1885), The Revised Standard Version (RSV 1952), The New American Standard Bible (NASB 1971) or The English Standard Version (ESV 2001).

(2) The dynamic or functional equivalence translation is not so much concerned with the original wording as with the original meaning and the impact it had on the original readers, e.g., The New English Bible (NEB 1970), The New International Version (NIV 1978), The Revised English Bible (REB 1989), The Good News Bible (GNB) or Today’s English Version (TEV 1976), and The Contemporary English Version (CEV 1995).

What is often considered a third type of translation, the paraphrase Bible, is more of a commentary than a translation. It seeks to restate in simplified but related ways the ideas conveyed in the original language, e.g., The New Testament in Modern English, by J. B. Phillips (NT, 1958), The Living Bible (1971), The Clear Word (1996) The Message (NT, 1993, OT 2002). For example, Colossians 2:9 “For in Him dwells all the fullness of the Godhead bodily” (NKJV) in The Message is expanded to “Everything of God gets expressed in Him, so you can see and hear Him clearly. You don’t need a telescope, a microscope, or a horoscope to realize the fullness of Christ, and the emptiness of the universe without Him.”

The first two types of translations are generally done by committees; paraphrases are done by one person who is skilled in literary style, but not necessarily in biblical languages. In spite of the fact that functional equivalence translations do not translate word for word, they try to translate every unit of meaning and function, whereas a paraphrase does not attempt an exact correspondence in units between the original and the paraphrase. In other words, whereas a paraphrase must render only the general idea of a passage, a functional equivalence translation is bound by more explicit standards of accuracy.

The formal equivalence translation

The advantage of a literal/formal equivalence translation is that it comes closest to the original text and it allows readers familiar with the original languages to see how idioms and rhetorical patterns are rendered. The major weakness of a formal translation is that a word for word translation produces some awkward sentences and can at times be misleading. For example, Genesis 12:19, “Why saidst thou, She is my sister? so I might have taken her to me to wife” (KJV) is literally what the Hebrew says, but it is not good English. In the New Testament the King James Version translates Titus 2:13 as “Looking for that blessed hope, and the glorious appearing of the great God and our Saviour Jesus Christ,” thereby splitting the terms “God” and “Saviour” and making one refer to the Father and the other to the Son. According to Greek grammar, however, the text should say “Looking for the blessed hope and the appearing of the glory of our great God and Savior, Christ Jesus” (NASB)—showing that Jesus is both our God and our Savior. Nevertheless, for serious Bible study it is best to select one of the newer formal equivalence translations such as The Revised Standard Version, the New King James Version, or The New American Standard Version.

The dynamic equivalence translation

An advantage of the dynamic/functional equivalence translation is that it is easier to understand. Its major weakness is that it involves more interpretation by the translators as indicated by the variant translations of many Bible passages. For example, the time period in Daniel 8:14 in Hebrew is literally 2,300 “evenings mornings” rather than “days.” The NIV has “2,300 evenings and mornings” the TEV, however, translates it as “1,150 days,” based on the interpretation that these are evening and morning sacrifices (i.e., 2,300 evening and morning offerings require 1,150 days). Yet, the KJV translation “days” is equally an interpretation (i.e., an evening and a morning equals one day), albeit one that is supported by other texts, such as Genesis 1:5, 8, 13, etc.

Most of the Greek manuscripts were found in monasteries, libraries, or ancient churches in Egypt, the Middle East, and in Europe. Codex Vaticanus (fourth century), thought to be the oldest (nearly) complete copy of the Greek Bible in existence, is believed to have reached Rome in 1483, during the Council of Florence, as a gift from the Byzantine Emperor Giovanni VIII to Pope Eugenio IV. Some manuscripts were found in the most unlikely places. More than fifty New Testament papyrus fragments, for example, were found in the ancient rubbish heaps of Oxyrhynchus in Egypt. Constantin von Tischendorf found about forty pages of Codex Sinaiticus (fourth century) in a trash bin in the convent of St. Catherine at the foot of Mount Sinai.

When giving Bible studies with a dynamic equivalence translation, care needs to be taken that the translation does not undermine the Bible study. For example, the NIV or CEV will not be helpful when the sanctuary truth is studied in the book of Hebrews because they use the incorrect term “Most Holy Place,” in Hebrews 9:8, 12, and 25, instead of “sanctuary,” which is used by the REB and NEB.

Whichever translation is used, we need to keep in mind that no translation is completely without interpretation. Therefore, we need to understand the strengths and weaknesses of each translation.

The underlying text

A second criterion concerns the underlying text from which the translation is made. The first complete English Bible, the Wycliffe Bible (c. 1380), was a translation of the Latin Vulgate; an early fifth-century version of the Bible in Latin. The Vulgate became the standard Bible of Roman Catholicism. During the Counter-Reformation the Vulgate was reaffirmed by the Council of Trent as the sole, authorized Latin text of the Bible. The Douay-Rheims Bible and the Ronald Knox translation were made from the Vulgate. In other words, they are translations of a translation.

The New Testament of the standard Protestant Bibles from Tyndale to the King James Bible were all based on the Received Text (Textus Receptus), which goes back to the Dutch scholar Erasmus (1466–1536), who published the first Greek New Testament in 1516. When Erasmus prepared his first edition of the Greek New Testament in 1515, he had only six manuscripts available to him, and since the last verses of Revelation were missing, he retranslated them from Latin into Greek. Today, there are over 5,000 Greek New Testament manuscript fragments attested, and many of the earliest papyri came to light only in the last hundred years.

The same is true of many Old Testament manuscripts. Until the discovery of biblical texts from the fifth century AD in the Cairo Geniza (a geniza is a store room in a synagogue) in the latter half of the nineteenth century, the oldest Hebrew Old Testament manuscripts were copied about a millennium after Christ. With the discovery of the Nash Papyrus (The Nash Papyrus contains the Decalogue and a portion of Deuteronomy 6:4, it dates to about 100 BC) in 1902 and the Dead Sea Scrolls in the beginning of 1947, Old Testament scholars finally obtained manuscripts containing parts of the Hebrew Old Testament that date from the time before Christ.

The primary value in these finds is that we have a much broader and better textual basis than the translators of the KJV had at their disposal. And although the age of a manuscript does not necessarily correspond to its accuracy, manuscripts that are a thousand years older than what was previously available must be taken into account. Most modern versions take advantage of the newly discovered Old and New Testament manuscripts.

The translator(s)

Another factor to consider is the competence of the translator(s). Just because someone publishes a translation of the Bible does not mean that the translator is competent for the task. In general, it is best to use translations done by committees rather than individuals.

Also, all translations reflect the presuppositions of the translators. These presuppositions may conform to a specific faith persuasion (e.g., Jewish, Catholic, Evangelical-Interdenominational, etc.) or be influenced by the scholarly views of the translators. It is useful to know the faith presuppositions of the translator(s), not in order to determine whether or not to avoid the translation but to be able to use it knowledgeably. Even though one may not agree with another religion or denomination, it may still be useful to read a translation done for that specific faith persuasion.

The intended audience

Some Bible translations are produced with specific audiences in mind. For example, the TEV made special efforts to be readable by someone whose first language is not English. Similarly, the NEB uses British English, and the NASB American English. J. B. Philips began a paraphrase of the New Testament epistles, later published as Letters to Young Churches in 1947, for the youth of his church during the bombings of England in World War II. He continued with other portions of the Bible and with later editions, but his later work became less paraphrased and less focused on a specific generation, especially as he recognized that his version was being more widely used. These are just a few examples showing the effect of the intended audience on a Bible translation. Knowing a translation’s intended audience also helps the reader to evaluate its appropriateness in various settings.

Summary

There is no substitute to being able to read the Bible in the original languages. When that is not possible, several translations should be compared with one another to make sure the text says the same in English as in the original languages. In order to evaluate a translation it is helpful to know what type of translation it is, what the underlying text was, who the translators were, and what intended audience they had in mind.

For serious Bible study it is best to use a literal translation that comes as close to the original text as possible (RSV, NASB, ESV, NKJV), as well as more dynamic versions that translate more the thoughts than the words of the original text (NIV, NEB, REB). For preaching and teaching in church a version should be used with which the listeners are familiar. For personal and family devotion a good paraphrase may sometimes be used. Paraphrases, however, should be avoided in Sabbath School or in the pulpit.

Finally, there is no “all-purpose best” translation. No single translation can fit all needs. However, understanding the various Bible versions and how and why they were translated is a means of helping one to know how to make the best use of them.